BRAINTREE HISTORICAL SOCIETY

- Home

- Lantern Online

- Lantern-Online September 2018

Thomas Watson’s Contributions to Education in Braintree (Part 2)

Thomas Watson’s interest in raising the standards of education in Braintree also seems to have applied to teachers. In 1892, the School Committee established a special teachers’ library to help teachers advance their own knowledge, and Watson himself presented a Guide to the Geology Collection in the Museum of the Society of Natural History, Boston to the new library (he also gave copies of this book to the reference libraries at the High School, Iron Works School, and the Monatiquot Grammar School). The Committee also instituted a plan to hold regular teachers’ meetings in order to discuss the latest developments in education in an effort to keep teachers us to date. Watson and the School Committee seem to have been striving to raise standards for teachers because they recognized the importance of his personal and intellectual standards in shaping children’s attitudes toward both education and life. The Superintendent’s report for 1899 echoes this sentiment:

Thomas Watson’s Contributions to Education in Braintree

By Jennifer Potts

Watson seems to have believed so completely in the vital importance of a teacher’s role in public education that he was willing to financially support Braintree in getting and keeping the best teachers. Watson encouraged teachers to pursue courses of study at educational institutions to improve their own knowledge and provided the funds for them to do so. In 1895, Watson’s generosity enabled the teachers to take two courses of lessons during the year. One of these courses in Mineralogy was held in April and May, and the other in Meteorology took place in November and December. In 1896, Watson’s generosity also allowed Braintree teachers to receive a course of lessons in voice culture (a special interest of Watson’s) from Mr. R.W. Cone of Boston. The Superintendent’s report of 1899 also gratefully acknowledges Watson’s financial commitment to getting and keeping good teachers in Braintree when it declared that: “We are under continued obligations to Mr. Thomas A. Watson for paying extra salaries of superior teachers, in one case at a rate of one hundred and fifty dollars a year to keep them from accepting other positions.”

Watson also donated books and equipment to the various schools in Braintree. In 1892, he donated an unabridged dictionary to the Iron Works Grammar School and a terracotta bust of Homer to the High School. In 1894, Watson presented a black walnut case with two hundred and seventy-five rock specimens from all over the world and thirty sets of thirty-five common rocks and minerals to the Jonas Perkins School. He also gave a set of rocks and minerals to the Union and Pond Schools for teaching purposes. In 1896, Watson also contributed pictures of Lincoln and Washington to decorate the classrooms of the Jonas Perkins School.

As part of his work for the School Committee, Watson also served on the building committees for three of Braintree’s schools; the Monatiquot School, the Jonas Perkins School, and the Penniman School. Watson was the chairman of the building committee for the Monatiquot Schoolhouse on Washington Street, which was built in 1892. The School Committee visited and studied the newest school buildings within a thirty mile radius of Boston before hiring the Boston architectural firm of Loring and Phipps to design the new building. The new building was designed to accommodate about five hundred pupils and had eight classrooms, an assembly hall, two large waiting rooms, a lecture room, laboratories, and large offices for the School Committee and Superintendent of Schools. The building also contained the latest heating and ventilation equipment and a system of electric calling and signaling apparatus.

The new building was formally dedicated and transferred to the care of the School Committee on June 17, 1892. Watson was also chairman of the Building Committee for the Jonas Perkins School in East Braintree. In March 1893, Town Meeting appointed a special committee to study the school buildings in East Braintree, and, at the adjourned meeting the following April, the committee recommended that the old East Middle Street and Iron Works Schools be replaced by a new, more modern school building. This new school was to be built on the corner of Liberty and Commercial Streets on land that had once belonged to a former School Committee member, the Reverend Jonas Perkins (1700-1874). The committee again hired Boston architectural firm Loring and Phipps to design the building, which was opened and transferred to the control of the School Committee on November 9, 1894. The new Jonas Perkins School was officially dedicated on November 27, 1894, and would later play an important part in the educations of Watson’s own children. Watson’s oldest son, Thomas Bell Watson, graduated from Jonas Perkins on June 18, 1896, followed a year later by his sister, Helen. Watson’s other two children, Ralph and Esther, also graduated from the Jonas Perkins School.Watson found himself on yet another building committee for a new school in 1899, although this time he was not the chairman. This building committee was chosen by the town on March 20, 1899 to consider the location and estimate the costs for a new school building in the Middle Street area of the town. The committee made its report at a special town meeting on June 15, 1899; and the town voted to accept a parcel of land on the corner of Cleveland and Harrison Avenues which had been given by Norton Eugene Hollis for the purpose of building a school. Brockton architect C.L. Mitchell was chosen to design the new building which was completed, furnished and opened for school use on September 4, 1900. The new building was named the Penniman School, in honor of Norton Hollis’ mother, Mary Penniman. The Penniman School was formally dedicated and transferred to the School Committee on October 5, 1900. Watson’s outstanding contributions to education in Braintree were later commemorated in 1924 when the town opened a new school and named it the Thomas A. Watson School in his honor.

Watson also made a little recognized contribution to education in Braintree by providing educational opportunities for its adult population. Early in 1890, Watson met a young clergyman named Oliver Huckel, who was a pastor at the Union Congregational Church of Weymouth and Braintree. Despite an ingrained distrust of those connected with institutionalized religion, Watson seems to have warmed immediately to Hackle’s personality and described his as “delightfully human and, if he had any plan for saving my soul, did not inflict it on me”. Watson and Huckel became friends and both shared a deep love of poetry and literature. Watson’s contact with Huckel and their shared love of literature and learning inspired Watson to come up with the idea of establishing a community center that would serve local people by providing opportunities for learning and recreation.

Watson looked to the Y.M.C.A. in Boston as a model for this new local community institution; and his idea was so enthusiastically received by Huckel and several other local residents that Watson decided to try it out. Work on Watson’s new experimental institute, which he called “The People’s Institute,” officially started around 1890 when Watson rented a building in Weymouth Landing and equipped it with a parlor, gymnasium, game rooms, and reading rooms. The institute also offered lectures and entertainments, which were held in Huckel’s church building, and hired teachers to teach classes in elocution, mechanical drawing, penmanship, arithmetic, bookkeeping, and gymnastics. The Peoples Institute started out with about a hundred paying members and was, at first, enthusiastically received. Indeed, Watson had high hopes for the Institute because he even drew up plans for a new building. Unfortunately, the new building never became a reality because initial interest in the Institute declined so much that Watson was forced to close its doors after only four years. Although the People’s Institute was not the success Watson hoped it would be, it is nevertheless significant as one of Braintree’s early attempts at providing an environment that supported continuing education for adults.

Watson’s contributions to education I Braintree are numerous and important, and reflect his deep personal commitment to learning and education improvement for everyone. Under Watson’s influence and visionary leadership, the 1890’s marked a period of growth and dynamic change for Braintree’s schools. Watson viewed learning as a life-long process; and his broad-minded approach to it helped to shape the attitudes of Braintree’s citizens for the better.

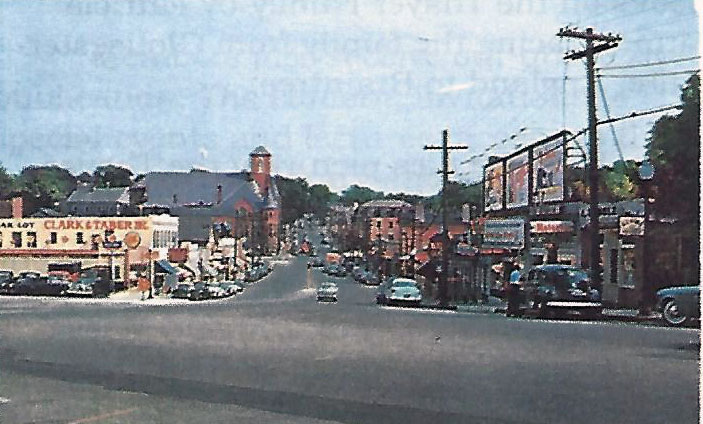

WEYMOUTH LANDING

THEN (from an old postcard)

WEYMOUTH LANDING

NOW