BRAINTREE HISTORICAL SOCIETY

- Home

- Lantern Online

- Lantern-Online November/December 2018

NOVEMBER/DECEMBER 2018

EDITOR'S NOTE:

We like to extend our thanks to Wayne G. Miller for his wonderful presentation recently regarding Shipbuilding in the area. With the November/December edition on the Lantern Online, we will continue with the shipbuilding theme.

We are also bringing to light, for some, another theme. It is the theme of the many contributions of Thomas A. Watson to the town of Braintree and the region. Those having read the Lantern Online September edition will note that during many of the years noted here, he was changing the lives of Braintree schoolchildren with his many contributions made during his time on the School Committee.

During our series about the history of our Braintree public schools it was mentioned the great contributions that Thomas A. Watson made to the schools of Braintree. As it turns out, after the invention of the telephone alongside Alexander Graham Bell and setting about serving on the School Committee and starting Kindergarten classes in Braintree, and thus the region, he then set about building his own shipyard in Braintree and again the results were life changing and improved for many.

Here we have a wonderfully detailed account of the Fore River Shipyard written and published in June, 2006 by our then Curator, Jennifer Potts. We extend our thanks for her wonderful contributions as well.

Thomas A. Watson:

Braintree’s Ship and Engine BuilderBy: Jennifer Potts

Thomas Watson (1854-1934) is probably most famous for co-inventing the telephone with Alexander Graham Bell, but did you know that this Salem-born inventor and businessman also founded what was to become one of the largest shipbuilding establishments in the country on his land in East Braintree? Watson’s shipbuilding business, which began as the Fore River Engine Company, provided employment to hundreds of local people and put Massachusetts back on the map as an important center of the shipbuilding industry in America.

In the spring of 1881 when Watson resigned his position as Head of Research and Development at the National Bell Telephone Company, establishing and running another company couldn’t have been further from his mind. Between 1875 and 1881, he had worked tirelessly to improve the telephone and had been the driving force behind the establishment of the Bell Telephone Company in 1877. The years Watson spent in the business had been the driving force behind the establishment of the Bell Telephone Company in 1877. The years Watson spent in the business had made him a wealthy man, and after he resigned to pursue other interests he decided to take an extended vacation to relax and explore Europe. Early in June 1881 Watson sailed out of East Boston for Liverpool, England, on the Batavia. He traveled extensively throughout Europe, visiting London, Norway, Denmark, Switzerland, Germany, France, and Italy before finally returning to the United States in May 1882. A few months later on September 5, 1882, Watson married Elizabeth Seaver Kimball of Cohasset and the couple went to California for their honeymoon. Initially the Watsons had planned to settle in California, but in March 1883 they decided to return to Massachusetts. Watson purchased a house and sixty acres of land along the Weymouth Fore River in East Braintree, and he and Elizabeth moved there in June 1883.

When he first settled in Braintree, Watson had intended to become a scientific farmer, but he quickly found that farming did not suit him and abandoned the idea. Casting about for a new interest, he decided that he missed the machine shop work of his early telephone days and longed to return to it. He got the chance to do so in the summer of 1883 when an old friend, Joseph Dennett, brought him some drawings of a new kind of rotary steam engine that had recently been invented by L.J. Wing of Lexington, Massachusetts. Watson was fascinated by the drawings, and during the winter of that year he visited the Boston shop where the first of these new engines was being built so that he could study the design. When the machine was tested in the spring of 1884, it had several major design flaws that Watson thought he might be able to fix. Watson then offered to build and try to improve the new engine and on October 11, 1884, he drew up an agreement to this effect with The Wing Rotary Engine Company. Watson lost no time in fitting up one of his old farm buildings as a machine shop and hired a young machinist, Frank O. Wellington, to help him build the engine. Watson and Wellington worked for several months to try to improve Wing’s steam engine but finally gave up in the spring of 1885 when Watson decided that the defects in the design were too great to be remedied.

Although the Wing engine had been a failure, Watson once again found himself in the machine shop environment he loved; and now he had a capable assistant that he wanted to keep, so he set about looking for something that he and Wellington could manufacture in their shop. He toyed with the idea of producing automobiles, but eventually decided instead to produce marine engines for yachts and tug boats. Watson made Wellington a partner in the business e now call the Fore River Engine Company. The company, which had started out with just Watson and Wellington, quickly built up a sterling reputation for innovative design and precise workmanship; and the business grew so rapidly that Watson had to build a larger building to accommodate up to thirty employees and all the necessary equipment. Watson had initially wanted to keep the business small so that he could work in the shop himself, but as his business prospered he once again found himself back in a supervisory position and in charge of bookkeeping.

Several years later, during the last 1890s, Watson made the momentous decision to increase the workload of his engine business by taking on contracts to build ships. Curiously, Watson’s decision to build ships seems to have been motivated more by humanitarian concern than profit, which was rather unusual for a turn-of-the century businessman. Watson sheds some light on his motivations on page 212 of his autobiography Exploring Life:

"The contrast between my lot in life and that of many of my neighbors had troubled me ever since I had lived (in Braintree) and in these times of general unemployment, the difference was more painful than ever, I tried to ease my conscience with gifts of money, coal, groceries, etc. too the sick and unfortunate of the vicinity but it seemed better to help by giving employment in our shop to as much of the unskilled labor of the region as we could us"

The Fore River Engine Company got its first contract with the U.S. Navy in 1897 to build two destroyers, the Lawrence and the Macdonough. This contract for $562,000 was completed in 1900 and represented a crucial turning point in the life of the company. Watson had to drastically increase the size of the East Braintree plant with the addition of several new buildings, which he fitted up with all the necessary heavy machinery. The ships were delivered to the Navy in 1903 and Watson’s company was well on its way to becoming a major center of the shipbuilding industry.

The Fore River Engine Company soon got more contracts: In June 1899 they were awarded the contract for an unarmored cruiser, the Des Moines (launched September 20, 1902). Although the company was growing and prospering, the work for the naval contracts was extremely precise and difficult, and needed to be inspected by the Navy at every stage. Watson’s financial resources were also stretched to the limit because, as both President and Treasurer of the company, he found himself constantly being called upon to contribute his own money in order to keep construction going until government payments came through. In addition, Watson was also constantly devising new methods of bookkeeping to keep pace with his growing and changing business.

Watson soon found that his business had grown beyond the limits of his East Braintree plant and in 1899 he purchased a hundred acres of land at Quincy Point with the intention of building an even bigger shipyard that could compete nationally. While the new shipyard was under construction ships were sent between the two yards as necessary. Construction plans for the new shipyard also included a connection between the shipyard and the East Braintree stop on the New York, New Haven, and Hartford Railway. Work on the new railway line began in 1902 and it became operational in June 1903.

By February 1901, the Fore River Engine Company had grown beyond Watson’s wildest expectations and the Navy demanded that the company go public before further contracts could become available. The company incorporated on February 15, 1901, and changed its name to the Fore River Ship and Engine Company. After this, naval contracts for two more battleships, the Rhode Island and the New Jersey, were signed. The Fore River Ship and Engine Company published its first prospectus on April 2, 1902, and shares sold at $100.00 per share. In addition to its work for the Navy the Fore River Ship and Engine Company also build merchant ships. These included the schooner Thomas W. Lawson (the largest schooner ever built at the time and the only one equipped with seven masts and twenty-five different sails), the William L. Douglas, and two Fall River Liners, the passenger steamer Providence and the freighter Boston. Watson’s company also built a new bridge over Quincy Point for the county in 1901.

The early 1900s were important years for Watson’s company, but extremely difficult and stressful for him personally. The shipyard required a great deal of money to keep it operating, and, as he waited to receive payment for completed contracts, Watson found that his own financial resources were constantly being stretched to the limit by its demands. Although Watson had hired a treasurer to take over the bookkeeping part of the company’s operations, the man had a nervous breakdown from the stress of the job, forcing Watson back to being both President and Treasurer.

In addition to the job stress, Watson also lost two of his four children. His oldest son, Thomas Bell Watson, died 1901 after a lingering illness (probably tuberculosis), followed two years later by his other son, Ralph Kimball Watson. Despite his personal difficulties Watson pressed on, but by 1902 he was unable to come up with any more of his own money to pump into the shipyard. He managed to secure a loan for $1.25 million dollars from the Adams Trust Company of Boston; but as a part of the deal he was forced to turn over a large bonus in preferred stock, surrender majority control of the Board of Directors, and agree to step down as President at any time. Watson accepted these terms to keep the shipyard going, and in June 1903 the Fore River Ship and Engine Company was awarded another naval contract to build the battleship Vermont. This would be the last contract that Watson would negotiate for the shipyard.

Watson’s days as President finally came to an end in October 1903, when the company was reorganized and he was replaced by a retired naval officer, Admiral Francis T. Bowles. Although Watson was elected Chairman of the Board of Directors, he resigned two months later and exited the ship and engine building business for good. Despite his somewhat unceremonious replacement after many years of dedication and financial sacrifice, Watson does not seem to have been bitter. With his characteristic optimism, he recalled being “pleased with their choice of president and felt that the Company was lucky to get such a man for the colossal task.” In his autobiography, Watson also tried in his characteristic way to downplay the difficulties associated with the Herculean task of running a huge and busy shipyard; trying instead to take the best from the experience and look upon it as something to be remembered in a positive light:

"Looking at these tremendous structures representing the highest skill of mankind, I felt that in the entire list of human industries there is none comparable in grandeur with the building of a ship (…). And, as I look back twenty-five years later, on my ship-building days, its poetry is still so superb in my memory that, in spite of the tragic elements mingling with it – anxieties, losses, deaths- I cannot regret that this great experience was mine."

Freed from the stress of running the shipyard, Watson soon rebounded from his troubles and disappointments. He and his wife began studying geology at M.I.T. and eventually received degrees in the subject. Watson also devoted his later years to other passions, including music, public speaking, acting, writing, and painting; and he continued to lead a fulfilling and active life until his death on December 13, 1934, at the age of eighty. With his shipyard, Watson left the city of Quincy a rich economic legacy that long outlived him. The yard continued to produce quality ships and submarines under the leadership of the Bethlehem Steel Company and later General Dynamics Corporation, which launched the last ship in 1986. Although Watson’s shipyard has now passed into history, its memory endures as a tribute to the ingenuity and dedication of its founder.

EDITOR'S NOTE

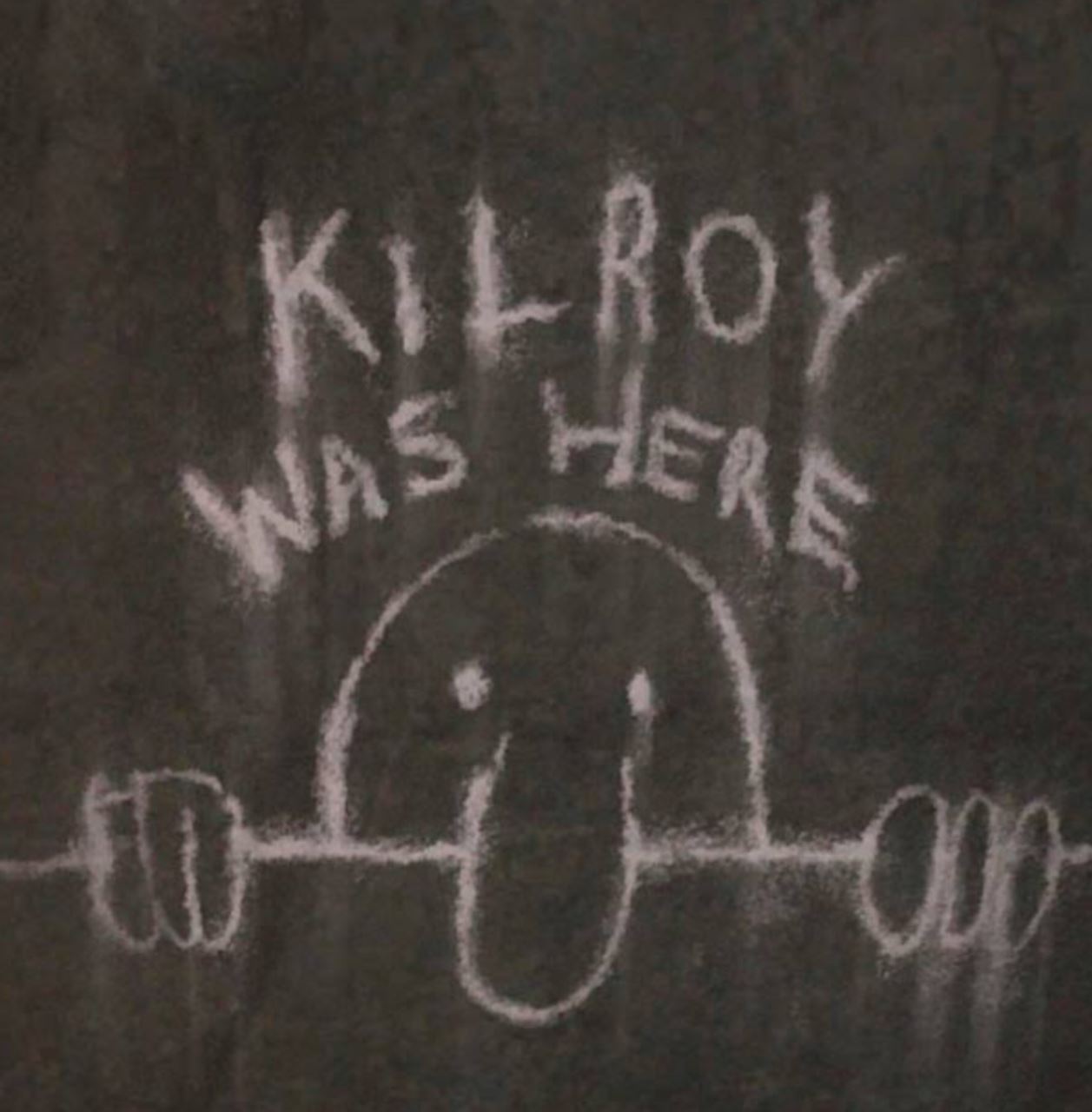

Though these events took place during WWII and were not related to Thomas Watson’s time at the shipyard, we thought it worth sharing. Here we have a story previously published in the printed Lantern in June 2006; the author was not noted at the time. We thought we’d use this as the “Then and Now” section due to the fact that these notices would not have changed over the years if there are still any to be had and is sure to put a smile on the faces of those who might have happened across these while serving their time.Kilroy & the Quincy Shipyard: The Origins of a Legend

Many of you who were around during World War II probably remember the phrase “Kilroy was here,” which appeared everywhere at the time, but do you know its origins? Well, James J. Kilroy of eponymous fame actually worked at the Fore River Shipyard in Quincy. He was hired on December 5, 1941 as a checker which meant that his job was to go around and check the work of the riveters, who got paid by the rivet. Kilroy would count the number of rivets and leave a chalk mark where he had left off so that the rivets wouldn’t be counted twice when the next checker’s shift began. Some of the less scrupulous riveters began to erase these chalk marks so that the next checker would recount Kilroy’s work, resulting in double pay for them. When Kilroy got wind of this devious scheme, he began to write “Kilroy was here” in big letters next to his mark, which made the whole thing more difficult to erase completely.

Normally, the rivets and any marks would have been painted over, but the demands of the war meant that ships were leaving the yard unpainted. Kilroy left his mark on many Quincy-built ships, including the Massachusetts, the Lexington, and the Baltimore, in addition to numerous troop carriers. When servicemen and crew entered the forgotten corners and sealed areas of these ships for maintenance and other tasks, they would find Kilroy’s mark and wonder about the mysterious Kilroy, who always seemed to have gotten there first.

Thus, Kilroy and his famous mark assumed a mythical status, and for the soldiers he came to represent the Super G.I. who had already been wherever they went. American soldiers wholeheartedly embraced the Kilroy legend and soon “Kilroy was here” began to appear wherever they went from Europe to Japan.

After the war, people began to wonder about the real Kilroy and in 1946 the American Transit Association sponsored a contest to try to find him. They offered a prize of a real trolley car to anyone who could definitively prove that he was the Kilroy. Although there were many pretenders, James J. Kilroy was able to prove that he was the genuine article by bringing along riveters and officials from the Quincy shipyard to back up his claim. He won the trolley car and had it set up in his front yard in Halifax, Massachusetts, as a playhouse for his nine children. Kilroy later went on to become a Massachusetts State Representative and Boston City Councilor. He died on November 26, 1962.

Kilroy & the Quincy Shipyard: The Origins of a Legend

Many of you who were around during World War II probably remember the phrase “Kilroy was here,” which appeared everywhere at the time, but do you know its origins? Well, James J. Kilroy of eponymous fame actually worked at the Fore River Shipyard in Quincy. He was hired on December 5, 1941 as a checker which meant that his job was to go around and check the work of the riveters, who got paid by the rivet. Kilroy would count the number of rivets and leave a chalk mark where he had left off so that the rivets wouldn’t be counted twice when the next checker’s shift began. Some of the less scrupulous riveters began to erase these chalk marks so that the next checker would recount Kilroy’s work, resulting in double pay for them. When Kilroy got wind of this devious scheme, he began to write “Kilroy was here” in big letters next to his mark, which made the whole thing more difficult to erase completely.

While we usually have photos of "Then and Now", we find that the

"Then" is also the "Now" with regards to "Kilroy".

Engraving of Kilroy on the National World War II Memorial in Washington, D.C.